What Happened to the Indigenous Human Remains that Were Displayed at the Southwest Museum?

A bust of the half Cherokee/half American scribe, Sequoyah at the Southwest Museum. All photos by Nathan Solis

[dropcap size=big]B[/dropcap]ehold the fortress-like Southwest Museum atop Mount Washington. Prior to the Autry Museum absorbing its collection of Native American Indian art there was the white tarp covering a burial display of ancestral remains inside the Southwest Museum's auditorium after a sit-in protest.

The Autry Museum of the American West inherited a 238,000-material collection from the Southwest Museum that includes artwork, religious artifacts, and human remains.

That’s right, the Autry received human cranial, long bone and other remains of indigenous peoples, as confirmed by L.A. Taco with Autry Director W. Richard West. Many of the remains are those of from indigenous tribes and bands that occupied the region before it was called Los Angeles or California.

The entire collection was moved in 2013 from Mount Washington to a climate-controlled facility in Burbank.

“They are there in the collection that we now have," said West. "We brought in representatives from local tribal communities to help with the move of the human remains. They were mostly Tongva people because we acknowledge we’re in their territory."

Autry Executive Vice President Maren Dougherty said, “I can tell you that the Autry, which merged with the Southwest Museum in 2003, has not, does not, and will not ever display human remains."

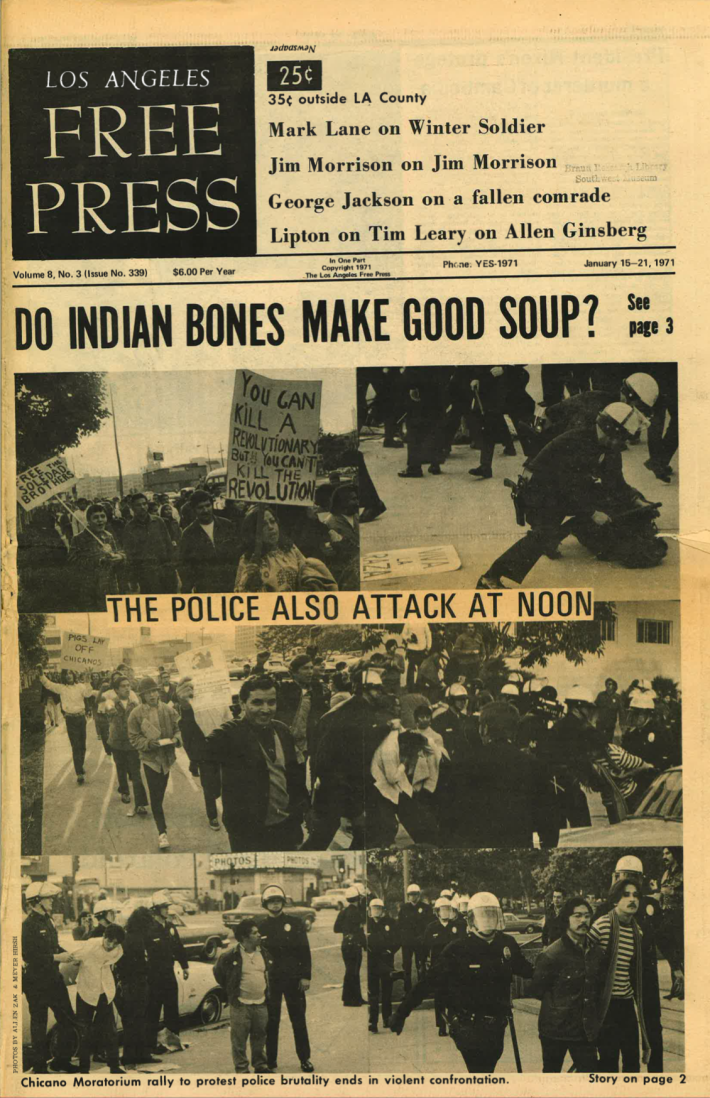

There was a time when that rule did not apply. Consider the afternoon of January 12, 1971, when a dozen protesters walked into the Southwest Museum, sat on the floor near a display of a Native American burial site, and chained themselves to a wall radiator.

Native American protesters and local Latino residents tried to have the displays removed, including religious artifacts and a braided hair from a Cheyenne scalp.

The display was covered by a white tarp.

For several weeks prior, Native American protesters and local Latino residents tried to have the displays removed, including religious artifacts and a braided hair from a Cheyenne scalp.

According to the Los Angeles Times, shouting matches erupted between museum officials and Native Americans who traveled across the country to protest.

When police arrived with bolt cutters to remove the protesters then museum director Carl Dentzel told the L.A. Times the protestors only objected to a few exhibits on a previous visit and the staff agreed to place a white tarp over the burial display.

“Now they want more, like the camel who got his nose in the tent,” Dentzel told the newspaper at the time. “We have never been graverobbers,” he went on to say. “The exhibits the Indians are objecting to have been considered outstanding anthropological exhibits here for more than forty years.”

Jerry Hill was 34 when he chained himself to the radiator. He remembers patrons looking through a glass window from outside to view their protest.

“They were expecting to see Indian art and then found Indians sitting inside,” says Hill, now 82 and a Chief appellate judge with the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin. “I don’t think we changed anyone’s mind, then and there. But we were coming of age in a time of consciousness,” Hill tells LA Taco.

In 1969, Hill spent two months on Alcatraz Island where Native Americans occupied the abandoned penitentiary to highlight the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which said retired federal land would be returned to the indigenous people who once occupied the land.

Today, the Autry Museum is in possession of the remains of 37 ancestors affiliated with federally recognized tribes and the remains of 131 people who are either from tribes not recognized by the federal government, or the person could not be connected to a tribe at all.

Meanwhile, in 1970 at the Chicano Moratorium, 30,000 demonstrators marched through East L.A. during the anti-Vietnam War protest. Four people were killed by police, including journalist Ruben Salazar, who was fatally struck in the head with a tear gas canister fired by a sheriff’s deputy.

There was a concentrated awareness for civil rights, says Hill who was arrested for trespassing at Southwest Museum. He says the experience made him want to become a lawyer.

Eventually, the offensive displays were removed and placed inside the museum’s tower.

Today, the Autry Museum is in possession of the remains of 37 ancestors affiliated with federally recognized tribes and the remains of 131 people who are either from tribes not recognized by the federal government, or the person could not be connected to a tribe at all.

For decades these ancestral remains resided at the Southwest Museum, but they’re not unique as institutions across the country have grappled with the same problem.

A 2017 audit of the federal government’s repatriation program shows there have been 185,475 individual sets of human remains identified by museums and institutions across the country since 1995.

The University of California, Berkley established an advisory committee to comply with federal law to repatriate human remains. For example, UC Berkeley has 7,769 sets of Native American human remains in its collection at the Hearst Museum of Anthropology, according to the most recent data available.

A 2017 audit of the federal government’s repatriation program shows there have been 185,475 individual sets of human remains identified by museums and institutions across the country since 1995.

Up until the 1980s, the Southwest Museum continued to accept artifacts and donations from excavations.

Most of the Southwest Museum’s ancestral remains belong to the Tongva people, the original pre-colonial residents of Southern California. By 2003 when the Autry absorbed the Southwest Museum, the collection was plagued by poor storage conditions and needed to be moved and cataloged.

The transfer took approximately six years.

“When you have an institution that has a collection that is over 100 years old, that is in a building with nooks and crannies, it’s hard to keep track of everything,” said Desiree Martinez, a professional archaeologist and Tongva community member who was hired by the Autry as a consultant.

The Southwest Museum in 2019

[dropcap size=big]T[/dropcap]he Southwest Museum no longer exists as it did during the sit-in, and West, the current Autry president, was hired in 2013, nearly 100 years after the museum first opened in Mount Washington.

When it came time to move the collection Martinez and other members of the Tongva community formed an advisory group to decide how they would break the chain of institutions overlooking tribal communities and they met at the Southwest Museum in 2017 over a three-day period.

Gabrielino/Tongva culture officer Julia Bogany, 71, who led a ceremony during the move at the museum, says the event felt empowering even though it begins the difficult duty of reburying a person.

“My hope is not to have to teach this skill to the next generation,” said Bogany.

Tribal communities across the country were notified by the Autry that one of the largest collections of Native American art was being moved. This could lead to the repatriation of ancestral remains under the government’s federal program Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act or commonly referred to by institutions, archaeologists and Native American communities as NAGPRA.

But this only happens after extensive research to confirm a person’s place of origin.

“We don’t want to haphazardly send someone to a community that we’re unsure about. We want to be sure that we’re sending them to their proper home,” Martinez said.

Previously, Native American Indians had little say about how institutions would treat their ancestor’s remains. West tells LA Taco that the incident in 1971 is startling, especially to him, a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

“It’s an important piece of history for any museum to recall this,” West said referring to the sit-in protest. “One of the challenges, which I sympathize and empathize with was the Southwest Museum’s capacities to deal with this question over the years on what to do with this collection. It was financially strapped and repatriation is a labor-intensive process.”

How Other Museums Have Dealt with Human Remains

[dropcap size=big]W[/dropcap]est formerly oversaw the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and also oversaw the repatriation process there. He says the Southwest Museum returned some ancestral remains in the 1990s, but the staff had limited resources to take on that task.

“It was not malice on their part,” West said. “We have indeed attempted to pick that up.”

NAGPRA depends on institutions to self-report, meaning the very institutions that once put up these displays are expected to begin repatriation.

Wendy Teeter, archaeology curator at the Fowler Museum at UCLA, says the museum has returned nearly 98% of its collection of human remains under NAGPRA.

That process began in 1993 when she took inventory of some 2,000 ancestral remains, including cranial bones and other human remains within the collection at UCLA.

“Most of the collection was archaeologically researched. It makes it simpler to know where this person came from and where they can go,” says Teeter.

Chief Anthony Morales from the Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe has seen several ancestors returned to his community from other institutions, but he knows there are many more with some likely in the Autry’s collection.

Repatriation under federal law depends on a federally recognized tribe working with the U.S. government. But for unrecognized tribes, like the Tongva community, there needs to be a partnership with a “cousin” tribe that is federally recognized.

Cultural resource director Joyce Stanfield Perry from the Juaneño Band of Mission Indians in California, who are not federally recognized, said it usually takes a long time for museums and institutions—two to five years—to comply with NAGPRA. “I just encourage that process to move forward for repatriation to move on. They need to be returned home,” said Perry.

Meanwhile, Chief Anthony Morales from the Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe has seen several ancestors returned to his community from other institutions, but he knows there are many more with some likely in the Autry’s collection.

Morales, 71, says this process will outlast him and his relatives.

“We’ve been patient,” Morales told L.A. Taco. “I don’t even know how to explain patient anymore. It’s been years. I’m hoping at some time these institutions get it together and comply with the deadlines with NAGPRA.”

An Autry spokesperson says most repatriations of human remains occurred between 2006 – 2009. The 41st repatriation of an individual from San Nicolas Island in the Channel Islands is expected to be completed later this year.

Earlier this year, the Autry announced it was seeking a new caretaker for the Southwest Museum campus. The new benefactor of the museum could continue to operate the site as a museum or something else.

How Much Does It All Cost?

[dropcap size=big]M[/dropcap]ost estimates for full rehabilitation and construction could be approximately $40 million, according to the Autry, but that doesn’t include additional costs for updating existing facilities, which could push the project over $50 million. The Autry is currently seeking funding sources should a new benefactor step forward.

Today, the museum, with its tower along the south of Mount Washington, is all but empty of its collection, save for a few objects.

When Jerry Hill chained himself to the radiator in 1971 he saw someone’s culture put up on display as though there were no other persons left alive to tell their story. It felt insulting. Like their world were a tale and they were robbed of their humanity.

“There was a plaque under the tomb they had there,” Hill said. “Trying to explain the story. What point does that do unless you say that all these people are gone? It was a display of how crude the human imagination could be. Those are just white man words.”

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from L.A. TACO

What To Eat In L.A. This Weekend: Mexican-Style Pastrami, ‘Trashburgers,’ and Flamin’ Jim Morrisons

Plus, a new shawarma spot in Tarzana and the country's first wine festival dedicated solely to orange "skin contact" wine happening in Hollywood.

The 11 Best Backyard Restaurants in Los Angeles

Despite many requests to publish this guide, L.A. TACO has been somewhat protective of these gems to not "burn out the spots." However, we wanted to share it with our small, loyal pool of paid members, as we appreciate your support (and know you to be okay, non-NARCs). Please enjoy responsibly and keep these 'hood secrets...secrets.

Here’s What an L.A. TACO Membership Gets You and Why You Should Support Local Journalism

With more than 30 members-only perks at the best L.A. restaurants, breweries, and dispensaries waiting to be unlocked, the L.A. TACO membership pays for itself!

Announcing the TACO MADNESS 2024 Winner: Our First Ever Three-Time-Champion From Highland Park

Stay tuned for the new date of our TACO MADNESS festival, which was unfortunately postponed this last Saturday due to rain.

What To Eat This Weekend: Cannabis-Infused Boat Noodles, Thai Smashburgers, and “Grass & Ass”

Plus, a pizza festival and a respected chef from Toluca, Mexico comes to Pasadena to consult for a restaurant menu, including enchiladas divorciadas, and more.