On a recent Friday evening, at the opening of a solo show by L.A.-based artist Pedro Pedro, I was invited to ask myself why I should steal a cow. Hanging on the far wall of the gallery, the cow in question leered in dumb, animal fear towards the entrance to West Hollywood’s New Image Art.

The show’s title, Why Should We Steal A Cow?, had my mind wrestling with the various motivations behind hypothetical ungulate larceny, but my eyes wandered elsewhere. For all its mass of muscle and hide, it’s bloodshot eyes and flared nostrils, it wasn’t the cow, but the quotidian objects adorning the gallery’s other walls that seemed to pulse with life.

Why Should We Steal A Cow? is a succession of vivid still lifes (the cow being one of three notable exceptions) that trace a couple’s struggle to subsist in the modern world, as well as their relationship to the objects that populate their domestic landscape. The show marks a dramatic shift to a more traditional style for Pedro Pedro, one that speaks to his newfound sense of comfort in both his adopted city and in his own skin. Familiar with the acclaimed artist’s body of work, I was less concerned with the question of why I should steal a cow, and more curious as to the lack of Technicolor genitalia.

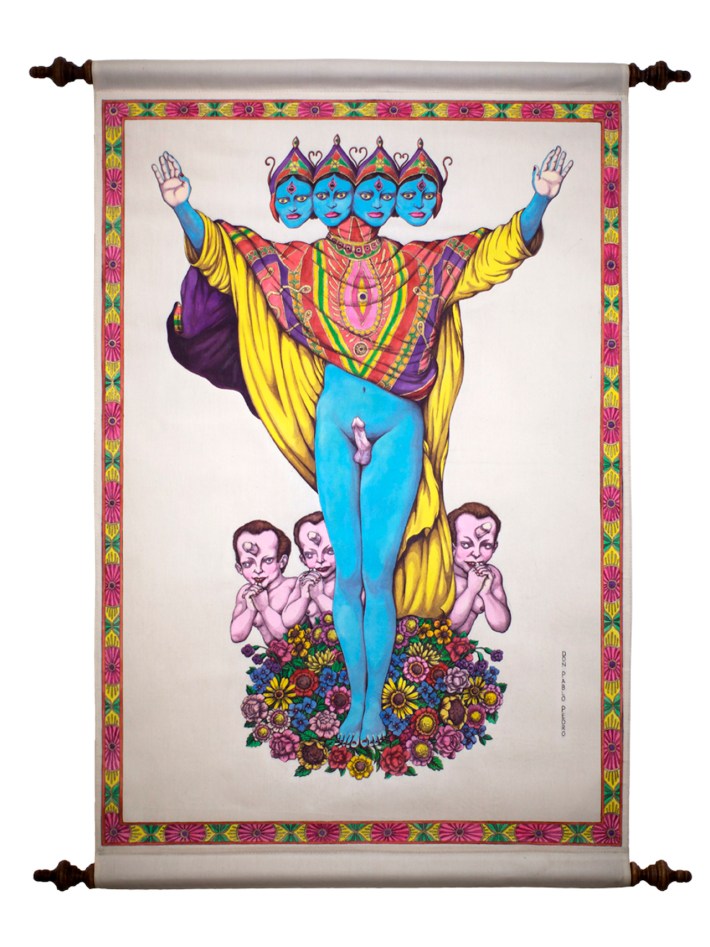

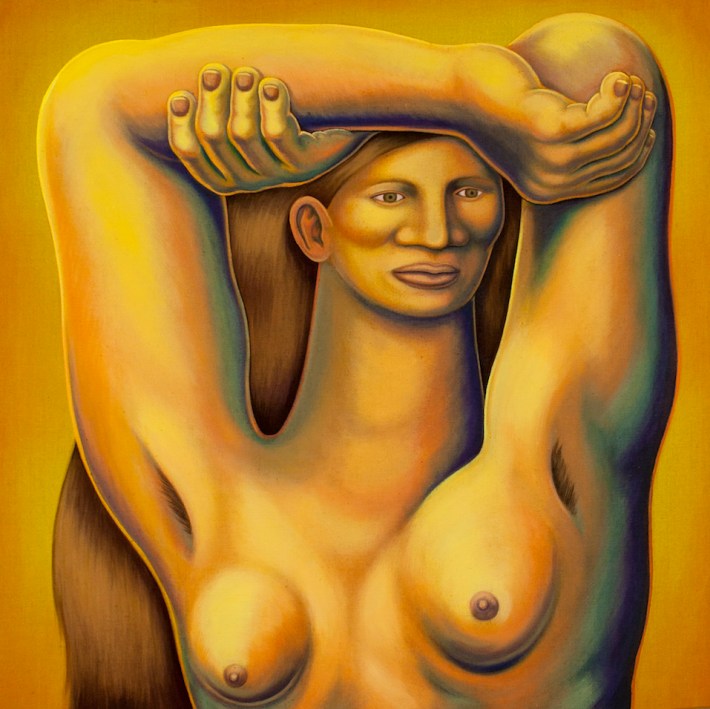

Pedro Pedro first found his artistic voice when he lost his left testicle. While recovering from an inguinal orchiectomy (med-speak for the removal of the offending ball), Pedro passed the sterile hours of convalescence painting and drawing on the sheets of his hospital bed. His affinity for painting on fabric followed him out of the hospital and into his then-New York studio. There he began repeatedly creating, warping, and grappling with the human form in dazzling works of numinous depravity.

Over the next several years, the exhibitions he held throughout New York were filled with multi-eyed, multi-headed, multi-genitaled pseudo-deities that leapt off muslin scrolls; with bearded blue figures vomiting naked bodies onto beds of flowers rendered on linen. This was Pedro’s world—one where the imperative to create was filtered through chaos and confusion, a too-vivid farrago that pulsed with defiant beauty in spite of its hedonism and deformity.

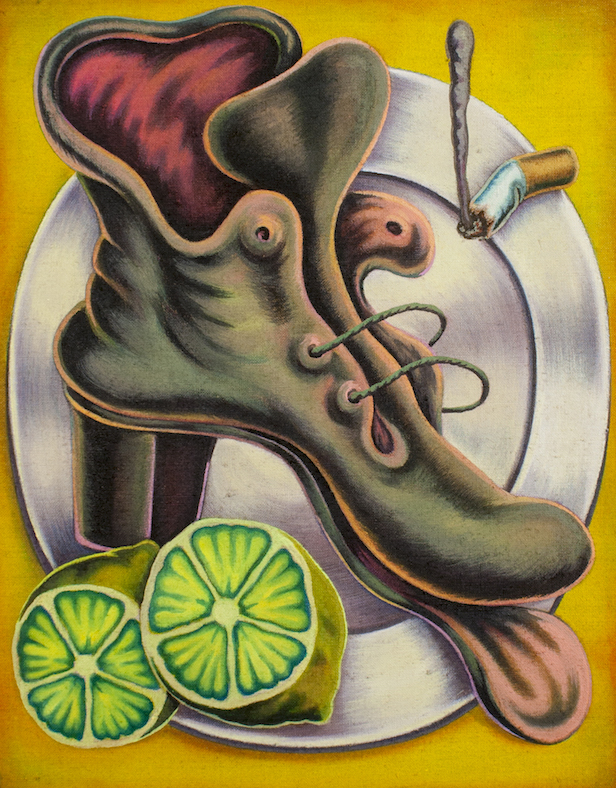

But upon leaving the roiling boroughs of New York City and relocating to L.A.’s Atwater Village, that world has changed considerably. Pedro has settled into a simpler life, rarely venturing further from home than the studio in his backyard. The mass of humanity that seethed around him back east has been replaced by mundane objects—fruit, keys, wine bottles in various states of fullness, a guitar, his girlfriend’s favorite pair of boots. They aren’t human or even humanoid, but rendered in Pedro’s hand, they are no less alive.

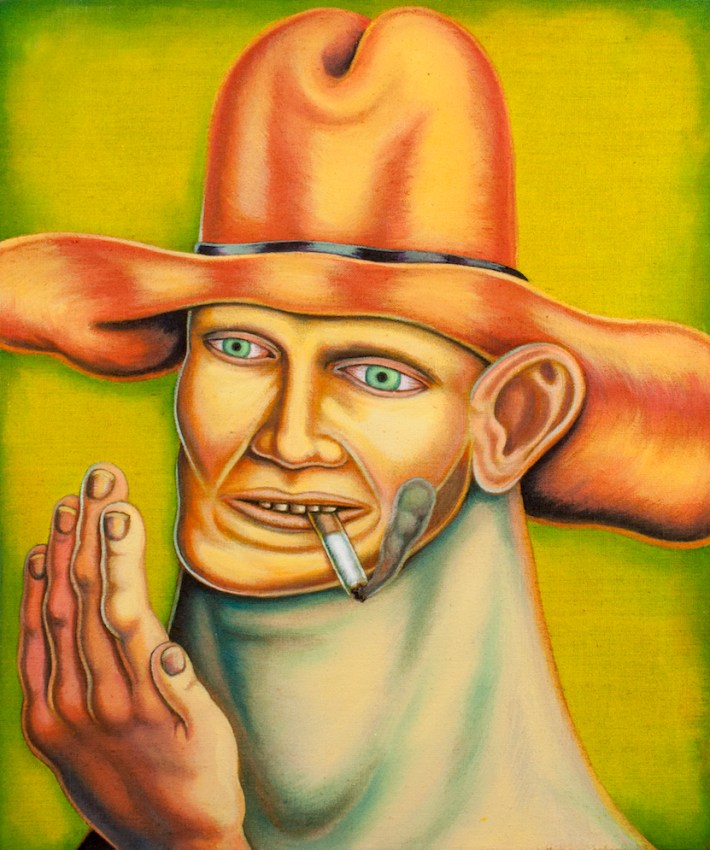

The artist became fascinated with the serene beauty objects display as they exist oblivious to their own entropy. He saw their assembly, function, and decay as a simple, yet purposeful life-cycle. As they accumulated in his studio, these studies into the lives of objects and their inherent vigor would become the paintings the comprise Why Should We Steal A Cow? The branches of “Flowering Plant 1” and “Flowing Plant 2” seem made of something closer to the flesh of his randy gods then ordinary bark; somehow the tableau of house keys, a fruit basket, and a wineglass repurposed as an ashtray found in “Still Life With Guitar,” pulses with a kinetic sexuality reminiscent of the demons often found fellating one another in Pedro’s earlier work.

Circumnavigating New Image Art, the story and paintings proved engrossing. Bolstered by Pedro Pedro’s technical skill, the sheer force with which objects pop off of his canvases is arresting. The sensuality of the food that comprises the couple’s epicurean diet conjures smells, textures, and a textbook-worth of Freudian associations. As the warped perspective of their dinner table threatens to spill precious calories into negative space, questions of stealing cows and colorful Vedic vulva fled my mind. I found myself wondering: who are these two people living together in a surreal desert? How do these objects seem to possess full-blown personalities? And why do all the cigarette butts have assholes?

After the opening, I caught up with Pedro Pedro at his studio to try and get some answers...

Why Should We Steal A Cow? will be up at New Image Art until March 31st. Contact or follow Pedro Pedro on Instagram @pedrosname

What’s your favorite taco spot?

There’s a taco truck across from the Griffin. That’s my favorite taco place I’ve ever been. I don’t know what it’s called, but it’s right across the street from the Griffin, in the car wash parking lot.

What’s your earliest memory?

I have no idea, truthfully. Something that stands out? I don’t know. My memory is shit. I have a hard time remembering anything at this point.

Is painting a way for you to catalog your memories? To keep from forgetting?

Yeah, yeah! Because everything I paint is from memory. All the still lifes—I’m not looking at anything when I’m painting. It’s all memory. That’s why they’re all a little off. They’re rendered out, but they’re slightly off because I’m trying to paint something from how I remember it.

That’s interesting because whenever the brain remembers something, it slightly distorts the memory. So, in a way your work is kind of replicating that internal process of remembering.

Yeah. Everything in the paintings is slightly distorted. A little bit off.

Can you remember the first thing you ever painted?

I guess when I was a kid—really young—I painted some boobs or something. I didn’t want to show my mom, but she found them and was like, “Who drew this?! Pedro, are you drawing dirty drawings?” I was like, “No! It was a friend of mine. It wasn’t me.” So I have that as a memory. But I always used to draw as a kid. Probably Ninja Turtles were my favorite thing to draw. So boobs and Ninja Turtles.

So even at a young age, your art has always had a sexual element to it.

I guess. Yeah, sometimes.

Do you know where that comes from?

I don’t know. I lost my testicle. Maybe that helps. Maybe that influences it. I don’t really know anymore. I’m trying to paint stuff that’s nice and pretty now. I want to paint pretty pictures. I don’t want to be vulgar anymore. I feel like it’s not necessary to do that.

I used to want, like, the shock value, but I don’t think the shock is important as much anymore. I think it’s just about making things that are pleasant. The world is so fucked so it’s better to make things that are pleasant rather than vulgar and offensive. I don’t really want to do that anymore. I’m trying not to offend anyone. I don’t want to offend anything.

But it was never sexual. It was always about form, about the figure of the body. Any of my dirtier drawings that I used to do, or paintings, there was no sexual thing to it. It was mostly just a form that I didn’t put clothes on. I didn’t really like painting fabric at the time. I wanted to paint flesh.

Now I’m trying to make something that feels more pleasant for myself. That’s more the direction that I’m trying to go for. Something that looks nice, that you feel good looking at. Other stuff I’ve done, it’s going to be hard to just sit with. [These new paintings are] a little bit easier to live with than some of the stuff I was doing in the past.

Did anything in particular prompt that stylistic shift?

I think it’s just the environment here. It’s a little bit chiller, a bit more relaxed. In New York everyone’s all on top of each other constantly. And that’s kind of what I was painting: these mangled figures all mashed together. I don’t have as much of that out here.

Did you feel inspired when you moved?

Yeah, of course. When I moved out of there, I moved to New York and I definitely felt inspired. There was art everywhere. Seeing all the street art, the graffiti, and meeting all those people who were creating out there was super inspiring.

How’s the transition from Nuyorican to Angeleño been going?

It’s good. I don’t drive, so that’s bad. But I love the weather. The weather fits me better than it did in New York. I’m not good with the cold, the damp and wet. The desert and the hotness suits me better.

Overall it’s great. I feel like I’m more positive. Where I’m living is great. It’s peaceful here. A little bit sleepier, a little quieter. Atwater’s cool.

But I have a hard time being in a city in general. I grew up in a small town and I kind of want to go back to that sort of thing. But it’s tough, finding a good small town community. I’d rather be around less action. Less noise.

Walk me through a typical day in the life of Pedro Pedro.

I usually wake up and cook breakfast for me and [my girlfriend] Kaitlin. A breakfast/lunch sort of deal. And then I go out here and I start futzing around with whatever I’m working on at the time—whether it’s a larger painting, or doing some smaller designs, or whatever else. And that’s pretty much my life. Just that every day, on repeat. Cook food for me and Kaitlin, come out here and do some painting.

I usually work from three in the afternoon to two in the morning.

There’s a lot of fruit in the paintings in your current show. Do you have a particular affinity for fruit? Or is this just you incorporating traditional elements of still lifes into your work?

I just started drawing fruit. They’re around—from cooking or whatever’s in the house. I just took ‘em and bugged out on them. Just warping them in strange ways and giving a more figurative dynamic to these objects.

I just like to bug out. I was bugging out on painting boots recently. I really liked painting boots because you can just do all sorts of weird stuff with them. I’m always looking around, like, “I can paint that. What can I do with that thing?” It’s not even really about the fruit. It’s about—whatever the objects are—what I can do with them. The colors I can use. The shapes. It’s not necessarily about the object as much as about how I can manipulate the color and shape.

How did the concept for behind Why Should We Steal A Cow come about?

Well, I came up with a title [for the show] and the gallerist was like, “Nah, the title’s no good.” Me and Kaitlin went to Samuel French, the play bookstore, and I was trying to think of a title. I’d painted these cow paintings and I had these still lifes and I wasn’t really sure how it all fit together. I opened a play, Modigliani, and the first line of it was: “Why should we steal a cow?”

Then I started putting all these paintings together and I saw them as this play or a movie where these two characters were tying to steal a cow to eat. But they’re kind of fuck ups. So they try to steal a cow, but they can’t do it and they end up eating a boot instead in some sort of apocalyptic world, some sort of other world. I was trying to take it away from things about myself and build this other narrative and this other world.

And also just Kaitlin being an actor—I was trying to use that. I saw that as my inspiration too. Being in L.A. probably has something to do with it as well…pretending like I’m making a play or a movie through painting.

Does your relationship tend to inform your work?

Kaitlin’s my inspiration for all of this stuff. Even some of the still lifes are like a stage, you know? The idea of being an actor—I couldn’t do it. I’m terrified of people. I need to hide in my hole as much as possible, away from the world. But I like to think about it, to stage all these characters, figures. Have them moving around, dancing.

Even the objects I paint. To me they move. They have this energy to them. I treat them as if they were a figure. Everything seems to have some sort of movement. It moves, it’s alive. Even if it’s just an object sitting on a table, it’s alive in some way.

Is that why the objects you paint have orifices and genitalia? The bananas have testicles or look even more phallic than real bananas tend to. The cigarettes have anuses, etc.

Well, everything kind of does, I guess. I’m smoking a cigarette and it’s shitting out smoke in my mouth. But yeah, they’re figurative still. I’m still stuck in that realm; it just translated into painting objects. They have everything that any animal or human has—which may be an anus, or whatever.

They have it all. The whole thing. They eat, shit, and die just like everybody else. Every object eats, shits, and dies. Everything’s living. This cup—I’m looking at it right now—it’s lived, it deteriorates, and it goes away like everything else.

Is there another mode of art besides painting that you feel informs your work?

I’ve been trying to learn how to play the guitar. I’m still really bad at it. I’ve been trying to play for fifteen minutes a day, so it’s going to take me a long time to get anywhere, but it’s better than nothing. It’s been fun.

What’s the craziest thing that’s happened to you thus far in your art career?

I guess when one of my paintings got stolen. That was a funny thing.

A painting got stolen from a show I did in New York. It somehow got all the way out to Roosevelt Island with all these college kids that had it. The painting was given to them by this guy around the corner form the gallery because he didn’t want the painting. So they took it on the train and brought it to Roosevelt Island.

I was freaking out all day. I was contacting everyone I could contact. I thought it was in the trash. And then these kids contacted me and they had it. We drove out to Roosevelt Island from Bushwick, picked up the painting, brought it back and hung it up the same day. So it was stolen and we got it back like 12 hours later.

It was like a five-by-four foot canvas, worth $3600 with a two-headed, fat, green dude getting his dick sucked on it, being hauled around the New York. When we got it back, there was no damage to it or anything. They brought it all the way on the train, there were photos of them on the train. That’s a funny story.

I just reread the Hyperallergic article about it the other day. People didn’t believe it was real; they thought it was fake. I almost didn’t believe it either. Like, how does that happen? Also, the painting was so weird. I don’t know who would steal a painting like that.

If you had to pick a single most important reason for humans to make art, what would it be?

Well, it’s always helped me out. Maybe it helps a lot of people out. I think it does. I think it’s a good thing to do. It’s underappreciated in a lot of ways. I think it’s just a great outlet to figure out who you are and what life is.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from L.A. TACO

An Update On Our Membership Drive: Some Bad News, and Good News

Some bad news, and some good news on our pledge to survive and stay sustainable.

Where To Eat This Weekend: Bulgogi Pupusas, Hemp Seed Guacamole, ‘Sticky Rice Sticks,’ and Korean Street Food In Venice

Plus an Roman chef veteran in a Hollywood apartment, chocolate Cuba Libres, Uzbeki plov with lazer rice, and cochinita melts in a Silver Lake yard. Here are the best things to eat around Los Angeles (and San Juan Capistrano!) this weekend.

How Your Business Can Benefit From Sponsoring L.A. TACO

When your company sponsors L.A. TACO, you receive a variety of quick and cost-effective benefits for far less than what we price our traditional advertisements and social media mentions at.

Juárez-Style Burritos Have Arrived in Southern California, And They are Already Selling Out In Less than An Hour

The month-old strip mall taquería in Anaheim make all their flour tortillas from scratch using both lard and butter, resulting in an extremely tender vehicle for their juicy guisados like carne en su jugo, carne deshebrada, chile colorado, chile relleno, and chicharrón. Every tortilla is cooked to order, too.